Taste of Arewa 4.0: Northern Nigerian Culture, Kanuri Wedding Traditions and Culinary Storytelling

Taste of Arewa is an annual fine dining experience that’s also a cultural project. It was created by Chef Maryam Ahmed, who is passion for food, sustainability and cultural heritage. She is also the founder of Mimies Homemade Sauces a food venture focused on celebrating and preserving Northern Nigerian cuisine.

Chef Maryam integrates modern techniques with traditional Arewa ingredients, aiming to ensure cultural food preservation for future generations.

Taste of Arewa 4.0 felt like entering a world where everyone shared the same awe at the decorations, the artworks carrying Arewa stories, and the sound of kakaki echoing through the lobby.

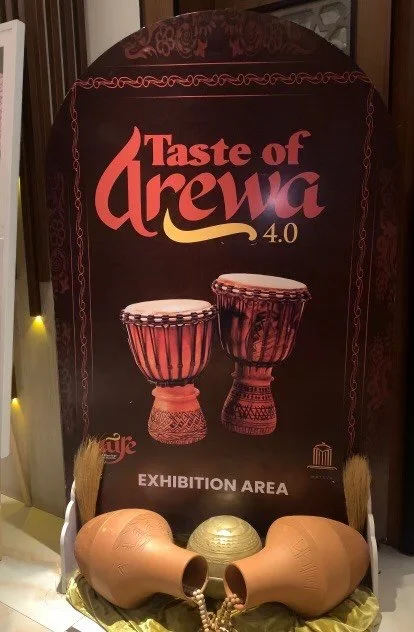

The Exhibition Area

The Kakaki, a very long metal trumpet used by Northern royalty for ceremonial events

The Kakaki, a very long metal trumpet used by Northern royalty for ceremonial events. Everyone was dressed very “Arewa” in their laces, saqi, tie-and-dye pieces, and atampas. It felt like the only right place to be. And because she sees food as storytelling, she approached this edition like an author building a book. Looking at the dishes, you could tell they were artworks, colours and textures symbolizing cultural practices that survived centuries.

A highlight from the menu, Masa Mezze - The Gathering

Fermented Rice pancake with Mezze Platter

A highlight from the menu, Masa Mezze—The Gathering Fermented Rice Pancake with Mezze Platter Food has always been a foundational part of cultural memory. And now, as globalization stretches its influence and conversations on heritage grow louder, chefs are becoming more intentional about using food as a medium of storytelling.

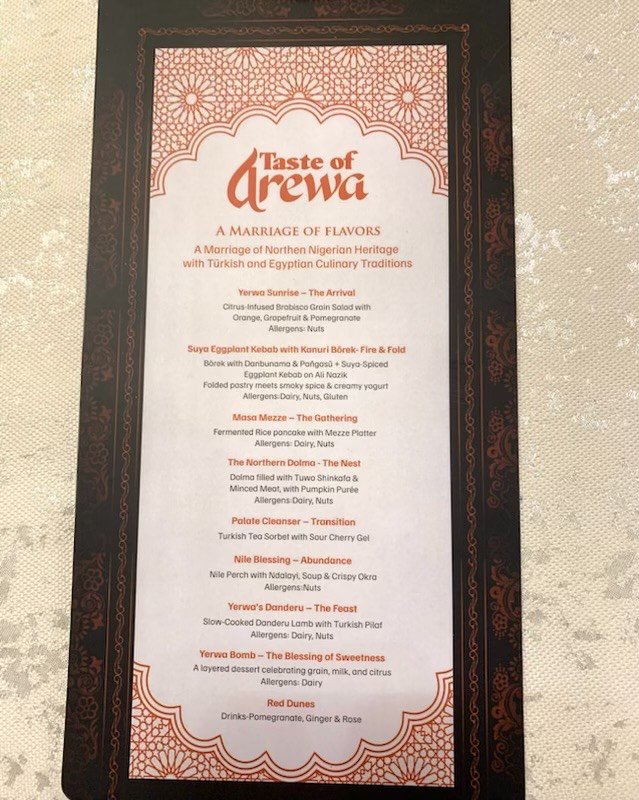

Nigerian meals have survived migration, colonial pressure, conflict and reinvention, yet they remain anchors of identity. This year’s theme, “Aure: A Marriage of Flavors,” traced the cultural parallels Chef Maryam drew from Istanbul, Cairo, and Yerwa (Borno), places that seem far apart but have always been connected through trade and shared traditions.

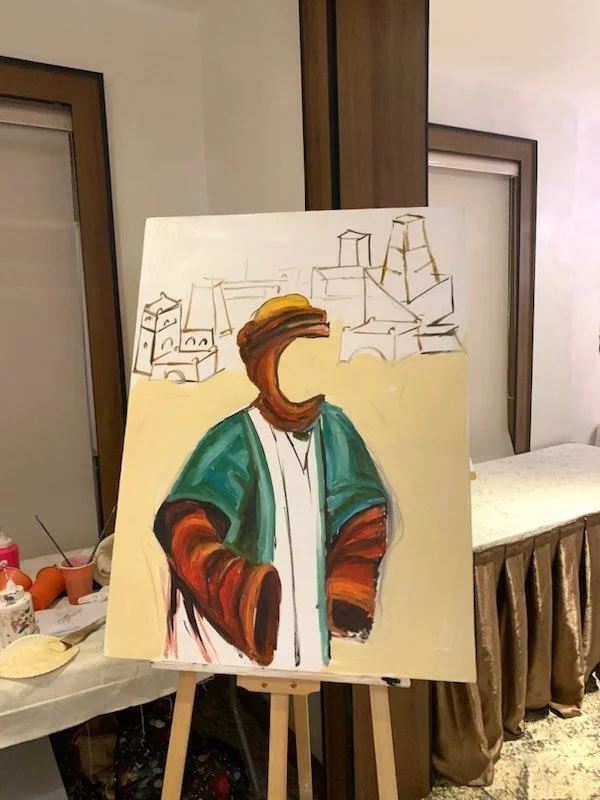

An ongoing live painting by Maryam Maigida which shows our lost history or parts of our history that was erased by time

Trade between the Ottoman–Turkish world and Northern Nigeria existed long before modern borders. This explains the similarities between Turkish and Northern Nigerian (especially Hausa and Kanuri) practices.

On her food tour through Istanbul and Cairo, she paid attention to how food is cooked, how spices are layered, the tea culture and the ways food connects to history. She found that they had so much in common with Northern Nigerian kitchens. Then she went to Borno, the core influence for this fusion.

Borno is one of the strongest cultural centres in the North. It’s a place that has endured long periods of conflict and disruption, yet cultural systems remain intact.

Many social rituals continue as working systems and a means of survival for the Kanuri, along with communities like the Shuwa Arabs, the Babur, and the Marghi, just to name a few tribes. Weddings, in particular, are central to their culture, as they compress lineage, craft, and ritual. Even after displacement or hardship, the rites continue to hold memory. Borno’s cultural life has not just simply survived countless attacks; it remains active, economically and artistically.

Chef Mimie spent time learning its recipes and systems. By the time she was done, she was connecting patterns and building a menu out of them.

The menu for the evening

The menu for the evening That continuity is exactly what The Veil of Memory, the main art piece of the exhibition, painted by Ajus Bunu, captures. It reflects an heirloom garment and its accessories as a way of storing identity.

The painting was of her mother’s wedding outfit, a forty-year-old dress and ornaments passed down.

“Veil of Memory” by Ajus Bunu

“Veil of Memory” by Ajus Bunu

“All my sisters who have gotten married so far have worn it.”

“I left the figure faceless because it’s not about the individual... the outfit itself is the identity.”

This shifts the focus from a person to what they represent. Several symbols anchor the work. She described the necklace as a “heart within a heart.” The bangles are heavy silver, deliberately dense, signalling the seriousness of marriage. “If you wear it, it will actually weigh you down... it shows the weight and the significance of marriage.”

The hairstyle in the painting marks a stage in a woman’s life. Kanuri women have distinct hairstyles for each stage,young women, newly married women, after childbirth and older maturity. It’s in details like these that the deeper significance of events like Taste of Arewa becomes clear.

In some ways, they serve as cultural archives. Another exhibiting artist, Ibrahim Saliu, spoke about the inspiration behind his own painting. His work also documents lived culture. The story began in 2019, when he travelled to Maiduguri and met a woman whose image became his artwork. “I had to look for someone to translate because I couldn’t speak Kanuri,” he said. “She agreed after initially saying no, then I took the picture and I came up with this.”

A portrait by Ibrahim Saliu capturing the beauty and heritage of Kanuri women

A portrait by Ibrahim Saliu capturing the beauty and heritage of Kanuri women To him, art acts as a bridge, especially for young people who may never visit certain places because of insecurity.

“They are still able to see how different people live their lives.”

His work captures a way of living younger generations might never witness firsthand. This is cultural memory made visible.

The Sokoto Caliphate I by Maryam Maigida

Taste of Arewa is also about pushing back against the narrow stories told about Northern culture. Samira Mohammed, a guest and founder of the brand Sultana NG shared her thoughts on this “There’s this idea of conservatism that has clouded how colourful and regal the Arewa culture is,” she said.

To many non-Northerners, the first image of Arewa is strictness, a narrative which is reinforced by media.

“People see that first before they actually see our colourful culture,” she explained. Events like this forcefully and intentionally widen the frame. They remind people that our values and aesthetics stretch far beyond stereotypes. They protect our past, correct our narratives, and invite new generations to learn and take pride in where they come from.