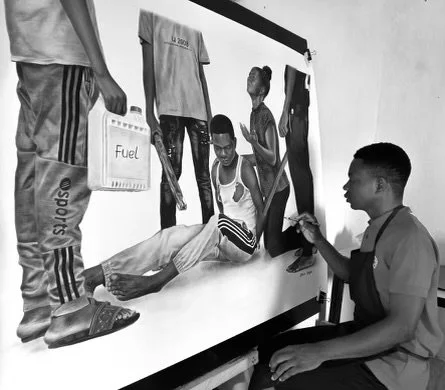

Stephen Nwofoke’s Hyperrealistic Approach to Drawing Human Emotions

Human emotion often reveals itself before words arrive, sometimes even more clearly than speech.

For visual artist Stephen Nwofoke, this language is where his work lies.

Stephen Nwofoke is an artist who creates charcoal and graphite portraits focused on human emotion. His drawings pay close attention to expression, capturing feelings that are deeply familiar to people. Nwofoke began drawing at a young age, though he did not initially see art as a serious path. “When I was younger, it was just like making diagrams,” he explains. His relationship with art changed in 2018 after he encountered the work of Ghanaian hyperrealist artist. “I saw his artwork and I was marvelled,” he recalls. “I didn’t know that art had gotten to that level.”

Motivated by what he saw, Nwofoke decided to teach himself. He began practicing consistently, studying reference images, experimenting with materials and learning through trial and error. “I started practicing from January 2018,” he says. “By December 2018, I had reached the level of hyperrealism.”

Over time, he realized that hyperrealism could be used to communicate the large range of emotions that humans experience.

“I was just creating portraits without knowing I could actually use art to tell stories,” he says.

“Then I started doing that.”

For Nwofoke, emotion is the most important, yet difficult part of his work “Drawing emotion requires a special technique,” he explains. “If the tones are not right, the story will not come through.” Among all emotions, sadness is the hardest to capture. “Happiness is easy,” he says. “Once the mouth is lifted and the teeth are showing, the smile is there.”

Sadness, however, is less obvious. “Sadness can be found in the eyes. It can be in the forehead.” To achieve this level of detail, Nwofoke follows a careful process. He does not rely solely on imagination when creating realistic portraits. “For hyperrealism, I don’t draw from imagination,” he says. “It’s very difficult.” Instead, he begins with an idea, sketches it out, and then works with a photographer to capture the exact pose he needs.

“I tell the photographer the pose I want then I draw from that.”

This approach allows him to control expression. “The reference helps me capture the emotion correctly.”

Before fully committing to visual art, Nwofoke enjoyed writing. Storytelling has always mattered to him. Over time, however, he noticed a shift in how people engage with written content. “A lot of people don’t read,” he says. “You post an article, and once they see ‘see more,’ they scroll.”

Drawing became a way to tell stories that did not rely on long attention spans. “People are caught by what they see first,” he explains. “Once the artwork catches them, they want to know the story behind it.” This has shaped how he thinks about audience and impact. He does not expect viewers to interpret his work in exactly the same way he intended, but he hopes it opens space for reflection.

Spending years studying faces and emotions has also changed how Nwofoke relates to people in everyday life. As his work continues to evolve, so does the artist behind it. After teaching himself in an environment where he could not find guidance, he had to learn patience and commitment on his own.

He now teaches younger artists and shares knowledge he once had to figure out alone. Like many artists, Nwofoke experiences periods of low motivation. When drawing feels difficult, he turns back to writing. “If I don’t draw, I write,” he says. He compares the process to a familiar saying: “When fishermen don’t go to the water to fish, they sit by the shore and mend their nets.”

Writing, for him, becomes a form of preparation. “Those stories, I can use them later to make art,” he explains. Stephen Nwofoke continues to create, refine his technique, and share his work. While his practice continues to evolve, his focus remains clear. “Emotion is what I’m after,” he says. “That’s what makes the work meaningful.” In a time when images move quickly and attention is fleeting, his drawings ask viewers to slow down to look closely and to feel something familiar reflected back at them.